Meymand Village

Maymand is a self-contained, semi-arid area at the end of a valley at the southern extremity of Iran’s central mountains. The villagers are semi-nomadic agro-pastoralists. They raise their animals on mountain pastures, living in temporary settlements in spring and autumn. During the winter months, they live lower down the valley in cave dwellings carved out of the soft rock (kamar), an unusual form of housing in a dry, desert environment. This cultural landscape is an example of a system that appears to have been more widespread in the past and involves the movement of people rather than animals.

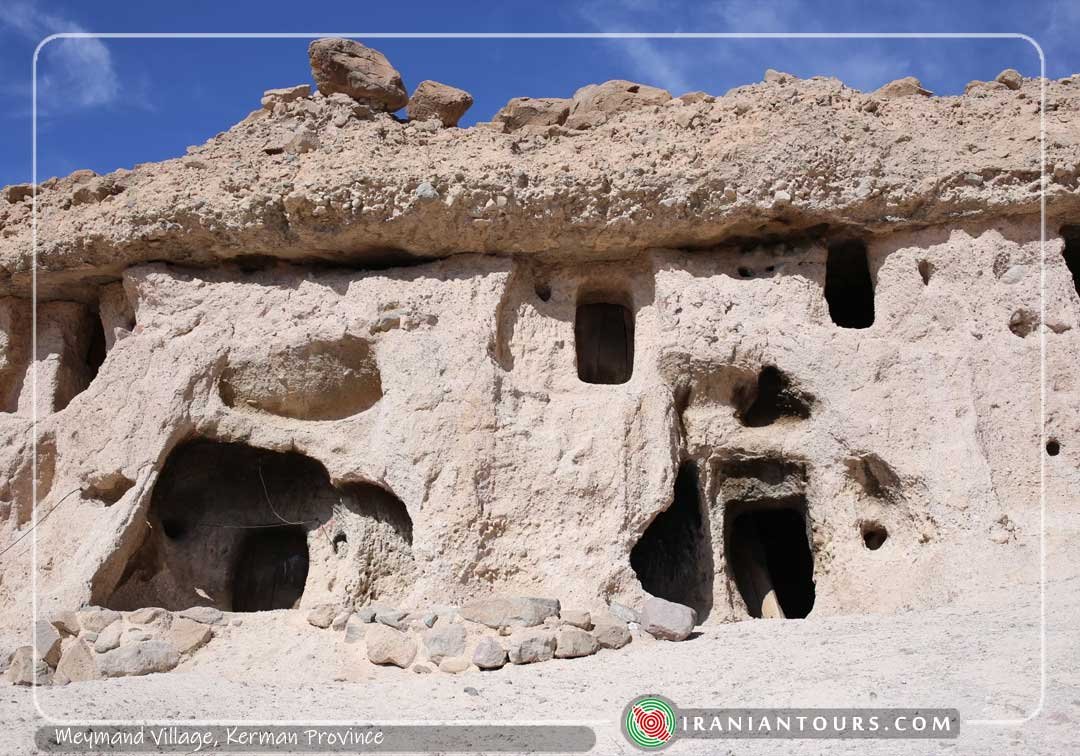

Maymand is a small and relatively self-contained south-facing valley within the arid chain of Iran’s central mountains. The villagers are agro-pastoralists who practice a highly specific three-phase regional variation of transhumance that reflects the dry desert environment. During the year, farmers move with their animals to defined settlements, traditionally four, and more recently three, that include fortified cave dwellings for the winter months. In three of these settlements the houses are temporary, while in the fourth, the troglodytic houses are permanent.

Sar-e-Āghols are the settlements on the southern fields used from the end of winter until late spring. The houses come in two different types. Markhānehs are circular houses, semi-underground to shelter them from the wind, with low dry stone wall and a roof covering of wood and thatch of wild thistles. Mashkdān houses are above ground and built with dry stone walls and a conical roof of branches. Some of the buildings for cattle are much more substantial and have barrel-vaulted brick or stone roofs.

Sar-e-Bāgh houses are sited near seasonal rivers and used during summer and early autumn. When the weather is hot the structures are light: dry stone walls support a roof structure of vertical and horizontal timbers covered with grass thatch. In inclement weather, more substantial houses are constructed with taller stone walls and a conical roof. Cattle are collected in roofless stone enclosures. Around these summer villages are the remains of terraces for growing wheat and barley, and the remains of mostly now ruined water-mills. Pits for boiling and straining grape juice are still in use as are Kel-e-Dūshāb which are used to contain the resulting Dūshāb or syrup of grapes.

The winter troglodytic houses are carved out of the soft rock, in layers of up to five houses in height. Around 400 Kiches or houses have been identified and 123 units are intact. Each house has between one and seven rooms, traditionally used for living, and storage.

In the exceptionally arid climate, traditionally every drop of water needed to be collected from a variety of sources such as rivers, springs and subterranean pools and collected in reservoirs or channelled through underground qanats to be used for animals, orchards and small vegetable plots. The community has a strong bond with the natural environment that is expressed in social practices, cultural ceremonies and religious beliefs.