Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque

Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque is one of the architectural masterpieces of Iranian architecture that was built during the Safavid Empire, standing on the eastern side of Naghsh-i Jahan Square, Esfahan, Iran. Construction of the mosque started in 1603 and was finished in 1619. It was built by the chief architect Shaykh Bahai, during the reign of Shah Abbas I of Persia. On the advice of Arthur Upham Pope, Reza Shah Pahlavi had the mosque rebuilt and repaired in the 1920s.

Of the four monuments that dominated the perimeter of the Naqsh-e Jahan Square, this one was the first to be built.

The purpose of this mosque was for it to be private to the royal court (unlike the Shah Mosque, which was meant for the public). For this reason, the mosque does not have any minarets and is smaller. Indeed, few Westerners at the time of the Safavids even paid any attention to this mosque, and they certainly did not have access to it. It was not until centuries later when the doors were opened to the public, that ordinary people could admire the effort that Shah Abbas had put into making this a sacred place for the ladies of his harem, and the exquisite tile-work, which is far superior to that covering the Shah Mosque.

To avoid having to walk across the Square to the mosque, Shah Abbas had the architect build a tunnel spanning the piazza from the Ali Qapu Palace to the mosque. On reaching the entrance of the mosque, one would have to walk through a passage that winds round and round, until one finally reached the main building. Along this passage, there were standing guards, and the obvious purpose of this design was to shield the women of the harem as much as possible from anyone’s entering the building. At the main entrance, there were also standing guards, and the doors of the building were kept closed at all times.

Today, these doors are open to visitors, and the passage underneath the field is no longer in use.

Sheikh Lutfallah

Throughout its history, this mosque has been referred to by different names. For Junabadi it was the mosque with the great dome (Masjed-e qubbat-e ’azim) and the domed mosque (qubbat masjed), while contemporary historian Iskandar Munshi referred to it as the mosque of great purity and beauty. On the other hand, European travellers, such as Jean Chardin referred to the mosque using the current name, and Quranic inscriptions within the mosque, done by Iranian calligrapher Baqir Banai, also include the name of Sheikh Lutfallah. In addition, the reckonings of Muhibb Ali Beg, the Imperial Treasurer, show that the Imam’s salary came directly from the imperial household’s resources. All this suggests that not only was the building indeed named after Sheikh Lutfallah, but also, that this famous imam was among the first prayer-leaders for the royal court in this very mosque.

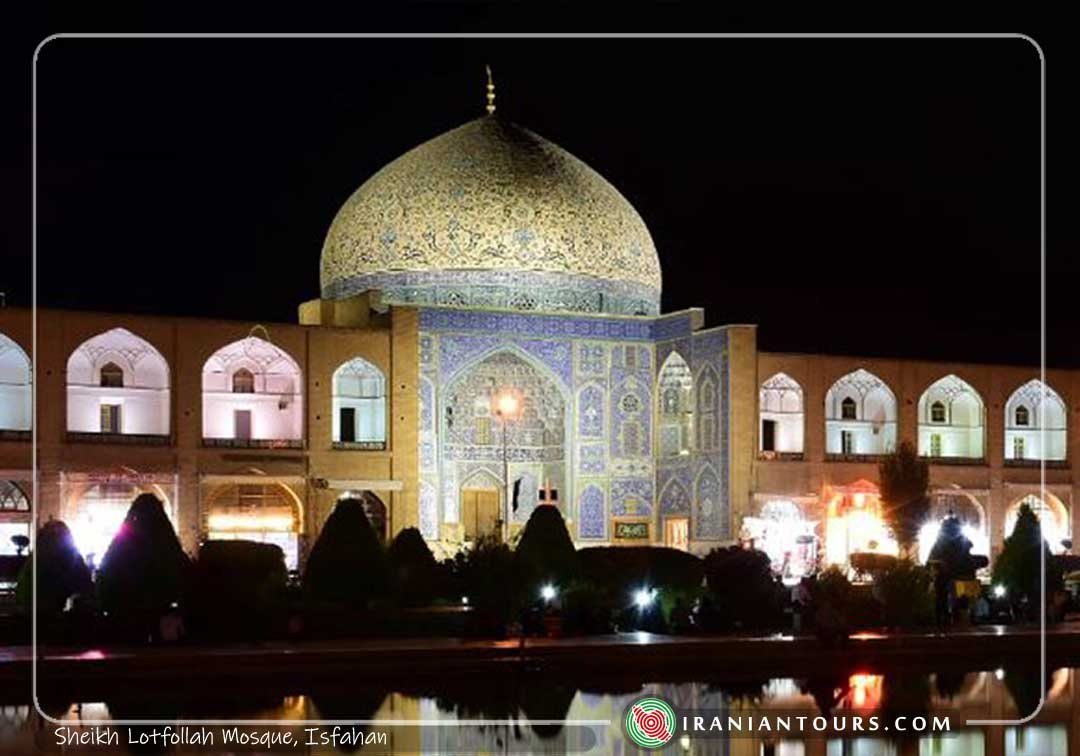

The entrance gateway, like those of the Grand Bazaar and the Masjed-e Shah, was a recessed half-moon. Also, as in the Masjed-e Shah, the lower façade of the mosque and the gateway are constructed of marble, while the haft-rangi tiles (lit. “seven-coloured”, “polychrome mosaics”) decorate the upper parts of the structure. The creation of the calligraphy and tiles, which exceed, in both beauty and quality, anything previously created in the Islamic world, was overseen by Master calligrapher Ali Reza Abbasi.

The monument’s architect was Mohammad-Reza Isfahani, who solved the problem of the difference between the direction of qibla and gateway of the building by devising an L-shaped connecting vestibule between the entrance and the enclosure. Reza Abbasi’s inscription on the entry gateway gives the date of the start of construction. The north-south orientation of the Maydan does not agree with the south-west direction of qibla; it is set at 45 degrees to it. This feature, called pāshnah in Persian architecture, has caused the dome to stand not exactly behind the entrance iwan.

Its single-shell dome is 13 metres (43 ft) in diameter. The exterior side is richly covered with tiles.

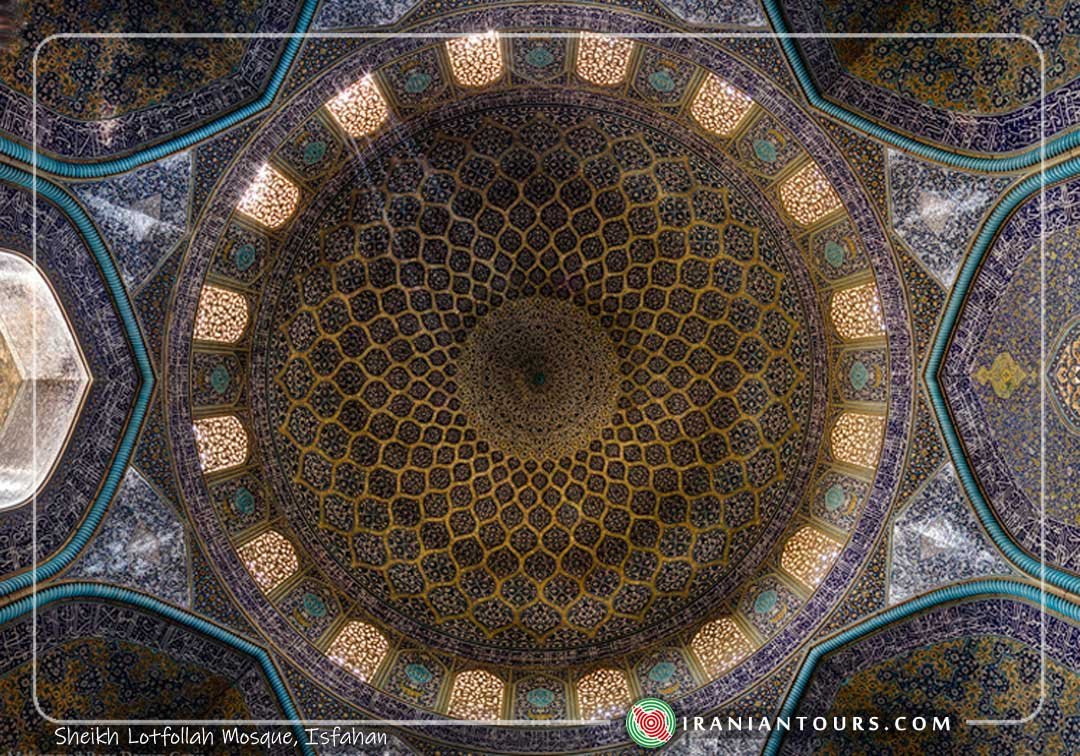

Compared with the Shah Mosque, the design of the Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque is quite simple: there is no courtyard, and there are no interior iwans. The building itself consists of a flattened dome resting on a square dome chamber. However, in contrast to the simple structure of this mosque, the decoration of both interior and exterior is exceedingly complex, and in its construction, the finest materials were used and the most talented craftsmen employed. Robert Byron wrote about this sight: I know of no finer example of the Persian Islamic genius than the interior of the dome:

The dome is inset with a network of lemon-shaped compartments, which decrease in size as they ascend towards the formalised peacock at the apex… The mihrāb in the west wall is enamelled with tiny flowers on a deep blue meadow. Each part of the design, each plane, each repetition, each separate branch or blossom has its own sombre beauty. But the beauty of the whole comes as you move. Again, the highlights are broken by the play of glazed and unglazed surfaces; so that with every step they rearrange themselves in countless shining patterns… I have never encountered splendour of this kind before.

The “peacock” at the centre of the interior side of the dome is one of the unique characteristics of the mosque. If you stand at the entrance gate of the inner hall and look at the centre of the dome, a peacock, whose tail is the sun rays coming in from the hole in the ceiling, can be seen.

At the interior side of the dome, the aesthetic purpose of the long, low, gloomy passage leading to the dome chamber becomes evident, for it is with a sense of heightened anticipation that one enters the sanctuary. Lowness gives way to soaring height and gloom is dispelled by the steady illumination of nearly a score of windows.

Barbara Brend described as follows: “the turquoise cable moulding of an arch is seen below the dome, in which concentric rings of thirty-two lozenges diminish in size as they approach a centre which gives an impression of luminosity. The design, which suggests both movement and stillness, is powerful though not an explicit vehicle of religious symbolism, speaking of the harmony of the universe. … The support system of the dome is illustrated by eight great arches of turquoise tilework in cable form which rise from a low dado to the full height of the wall, four in the position of squinches and four against the side walls; between them are kite-shaped squinches-pendentives. Within the dome, ranks of units of tilework of ogee-mandorla form are set in a lattice of plain brick and diminish in size until they meet a central sunburst patterned with a tracery of arabesque”.

The structure of the dome of Lotfollah mosque and that of Blue mosque of Tabriz is believed to be derived from that of Shah Vali mosque of Taft, Yazd.

The tiling design of this mosque, as well as that of Shah Mosque and other Persian mosques of even before Safavid period, seems to be not completely symmetrical – particularly, in colours of patterns. They have been described as intentional, “symmetrical” asymmetries.

Architects of the complex were Sheikh Baha’i (chief architect) and Ustad Mohammad Reza Isfahani.

The building was completed in 1618 (1028 AH).

Design of the Ardabil Carpet was from the same concept as that of the interior side of the dome. Also, the design of the “Carpet of Wonders”, which will be the biggest carpet in the world, is based on the interior design of the dome. It has been suggested that concepts of the mystic philosopher Suhrawardi about the unity of existence were possibly related to this pattern at the interior side of the dome. Ali Reza Abbasi, the leading calligrapher at the court of Shah Abbas, has decorated the entrance, above the door, with majestic inscriptions with the names and titles of Shah Abbas, the Husayni and the Musavi, that is, the descendants of Imams Husayn and Musa.

The inscriptions of the Mosque reflect matters that were preoccupying the shah around the time it was built; namely the need to define Twelver Shiism in contrast to Sunni Islam, and the Persian resistance to Ottoman invasion. The running inscription in white tile on the blue ground on the exterior drum of the dome, visible to the public, consists of three suras (chapters) from the Quran; al-Shams (91, The Sun), Al-Insan (76, Man) and al-Kauthar (108, Abundance). The suras emphasize the rightness of a pure soul and the fate in hell of those who reject God’s way, most likely referring to the Ottoman Turks.

Entering the prayer chamber, one is confronted with walls covered with blue, yellow, turquoise and white tiles with intricate arabesque patterns. Quranic verses appear in each corner while the east and west walls contain poetry by Shaykh Bahai. Around the mihrab are the names of the Twelve Shi’i Imams, and the inscription contains the names of Shaykh Lutfallah, Ostad Muhammad Reza Isfahani (the engineer), and Baqir al- Banai (the calligrapher who wrote it).

Turning right at the entrance to the domed prayer chamber, one first encounter the full text of Sura 98, al- Bayyina, the Clear Proof. The message of this chapter is that clear evidence of the true scripture was not available to the People of the Book (i.e. Christians or Jews) until God sent his messenger Muhammad. The horizontal band of the script at the bottom of the arch is not Quranic but states that God’s blessings are on the (Shi’i) martyrs. Thus, Shi’i invocation echoes the Quranic verses in its stress on the truthfulness of God’s message.

The poem of Shaykh Bahai on the right wall prays for help from the Fourteen Immaculate Ones (Muhammad, Fatima and the Twelve Imams), while the inscriptions on the interior of the dome emphasize the virtues of charity, prayer and honesty, as well as the correctness of following Islam and its prophets versus the error of other religions.

The specifically Shi’i passages and their prominent placement in the mihrab, on the two lateral walls and in the horizontal bands of each corner, underscore the pre-eminence of this creed in Safavid Iran.

The fact that two poems by Shaykh Bahai, a devoted Sufi, grace the walls of Shah Abbas’ private mosque, proves that, although some Sufi elements in the empire were suppressed, Sufism as a general phenomenon continued to play an important role in the Safavid society.

The design of the interior of the dome also inspired the design of Azadi Square in Tehran.