Timeline

The Akkadian Empire was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia, centred in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region, which the Bible also called Akkad. The empire united Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one rule. The Akkadian Empire exercised influence across Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Anatolia, sending military expeditions as far south as Dilmun and Magan (modern Bahrain and Oman) in the Arabian Peninsula.

During the 3rd millennium BC, there developed a cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism. Akkadian, an East Semitic language, gradually replaced Sumerian as a spoken language somewhere between the 3rd and the 2nd millennia BC.

The Akkadian Empire reached its political peak between the 24th and 22nd centuries BC, following the conquests by its founder Sargon of Akkad. Under Sargon and his successors, the Akkadian language was briefly imposed on neighbouring conquered states such as Elam and Gutium. Akkad is sometimes regarded as the first empire in history, though the meaning of this term is not precise, and there are earlier Sumerian claimants.

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, the people of Mesopotamia eventually coalesced into two major Akkadian-speaking nations: Assyria in the north, and, a few centuries later, Babylonia in the south.

Brief History

History and development of the empire

Pre-Sargonic Akkad

The Akkadian Empire takes its name from the region and the city of Akkad, both of which were localized in the general confluence area of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Although the city of Akkad has not yet been identified on the ground, it is known from various textual sources. Among these is at least one text predating the reign of Sargon. Together with the fact that the name Akkad is of non-Akkadian origin, this suggests that the city of Akkad may have already been occupied in pre-Sargonic times.

Sargon of Akkad

Sargon of Akkad defeated and captured Lugal-zage-si in the Battle of Uruk and conquered his empire. The earliest records in the Akkadian language date to the time of Sargon. Sargon was claimed to be the son of La’ibum or Itti-Bel, a humble gardener, and possibly a hierodule, or priestess to Ishtar or Inanna. One legend related to Sargon in Assyrian times says that

My mother was a changeling, my father I knew not. The brothers of my father loved the hills. My city is Azurpiranu (the wilderness herb fields), which is situated on the banks of the Euphrates. My changeling mother conceived me, in secret she bore me. She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen she sealed my lid. She cast me into the river which rose not over me. The river bore me up and carried me to Akki, the drawer of water. Akki, the drawer of water, took me as his son and reared me. Akki the drawer of water, appointed me as his gardener. While I was gardener Ishtar granted me her love, and for four and (fifty?) … years I exercised kingship.

Later claims made on behalf of Sargon were that his mother was an “entu” priestess (high priestess). The claims might have been made to ensure a pedigree of nobility since only a highly placed family could achieve such a position.

Originally a cupbearer (Rabshakeh) to a king of Kish with a Semitic name, Ur-Zababa, Sargon thus became a gardener, responsible for the task of clearing out irrigation canals. The royal cupbearer at this time was in fact a prominent political position, close to the king and with various high-level responsibilities not suggested by the title of the position itself. This gave him access to a disciplined corps of workers, who also may have served as his first soldiers. Displacing Ur-Zababa, Sargon was crowned king, and he entered upon a career of foreign conquest. Four times he invaded Syria and Canaan, and he spent three years thoroughly subduing the countries of “the west” to unite them with Mesopotamia “into a single empire”.

However, Sargon took this process further, conquering many of the surrounding regions to create an empire that reached westward as far as the Mediterranean Sea and perhaps Cyprus (Kaptara); northward as far as the mountains (a later Hittite text asserts he fought the Hattian king Nurdaggal of Burushanda, well into Anatolia); eastward over Elam; and as far south as Magan (Oman) — a region over which he reigned for purportedly 56 years, though only four “year-names” survive. He consolidated his dominion over his territories by replacing the earlier opposing rulers with noble citizens of Akkad, his native city where loyalty would thus be ensured.

Trade extended from the silver mines of Anatolia to the lapis lazuli mines in modern Afghanistan, the cedars of Lebanon and the copper of Magan. This consolidation of the city-states of Sumer and Akkad reflected the growing economic and political power of Mesopotamia. The empire’s breadbasket was the rain-fed agricultural system of Assyria and a chain of fortresses was built to control the imperial wheat production.

Images of Sargon were erected on the shores of the Mediterranean, in token of his victories, and cities and palaces were built at home with the spoils of the conquered lands. Elam and the northern part of Mesopotamia (Assyria/Subartu) were also subjugated, and rebellions in Sumer were put down. Contract tablets have been found dated in the years of the campaigns against Canaan and against Sarlak, king of Gutium. He also boasted of having subjugated the “four-quarters” — the lands surrounding Akkad to the north (Assyria), the south (Sumer), the east (Elam), and the west (Martu). Some of the earliest historiographic texts (ABC 19, 20) suggest he rebuilt the city of Babylon (Bab-ilu) in its new location near Akkad.

Sargon, throughout his long life, showed special deference to the Sumerian deities, particularly Inanna (Ishtar), his patroness, and Zababa, the warrior god of Kish. He called himself “The anointed priest of Anu” and “the great ensi of Enlil” and his daughter, Enheduanna, was installed as priestess to Nanna at the temple in Ur.

Troubles multiplied toward the end of his reign. A later Babylonian text states:

In his old age, all the lands revolted against him, and they besieged him in Akkad (the city) [but] he went forth to battle and defeated them, he knocked them over and destroyed their vast army.

It refers to his campaign in “Elam”, where he defeated a coalition army led by the King of Awan and forced the vanquished to become his vassals.

Also shortly after, another revolt took place:

the Subartu (mountainous tribes of Assyria) the upper country—in their turn attacked, but they submitted to his arms, and Sargon settled their habitations, and he smote them grievously.

Rimush and Manishtushu

Sargon had crushed opposition even at old age. These difficulties broke out again in the reign of his sons, where revolts broke out during the nine-year reign of Rimush (2278–2270 BC), who fought hard to retain the empire, and was successful until he was assassinated by some of his own courtiers. According to his inscriptions, he faced widespread revolts and had to reconquer the cities of Ur, Umma, Adab, Lagash, Der, and Kazallu from rebellious ensis: Rimush introduced mass slaughter and large scale destruction of the Sumerian city-states and maintained meticulous records of his destructions.

Most of the major Sumerian cities were destroyed, and Sumerian human losses were enormous:

Rimush’s elder brother, Manishtushu (2269–2255 BC) succeeded him. The latter seems to have fought a sea battle against 32 kings who had gathered against him and took control over their pre-Arab country, consisting of modern-day the United Arab Emirates and Oman. Despite the success, like his brother, he seems to have been assassinated in a palace conspiracy.

Naram-Sin

Manishtushu’s son and successor, Naram-Sin (2254–2218 BC), due to vast military conquests, assumed the imperial title “King Naram-Sin, king of the four-quarters” (Lugal Naram-Sîn, Šar kibrat ‘arbaim), the four-quarters as a reference to the entire world. He was also for the first time in Sumerian culture, addressed as “the god (Sumerian = DINGIR, Akkadian = ilu) of Agade” (Akkad), in opposition to the previous religious belief that kings were only representatives of the people towards the gods. He also faced revolts at the start of his reign but quickly crushed them.

Naram-Sin also recorded the Akkadian conquest of Ebla as well as Armanum and its king. The location of Armanum is debated: it is sometimes identified with a Syrian kingdom mentioned in the tablets of Ebla as Armi, whose location is also debated; while historian Adelheid Otto identifies it with the Citadel of Bazi at the Tell Banat complex on the Euphrates River between Ebla and Tell Brak, others like Wayne Horowitz identify it with Aleppo. Further, while most scholars place Armanum in Syria, Michael C. Astour believes it to be located north of the Hamrin Mountains in northern Iraq.

To better police Syria, he built a royal residence at Tell Brak, a crossroads at the heart of the Khabur River basin of the Jezirah. Naram-Sin campaigned against Magan which also revolted; Naram-Sin “marched against Magan and personally caught Mandannu, its king”, where he instated garrisons to protect the main roads. The chief threat seemed to be coming from the northern Zagros Mountains, the Lulubis and the Gutians. A campaign against the Lullubi led to the carving of the “Victory Stele of Naram-Suen”, now in the Louvre. Hittite sources claim Naram-Sin of Akkad even ventured into Anatolia, battling the Hittite and Hurrian kings Pamba of Hatti, Zipani of Kanesh, and 15 others. This newfound Akkadian wealth may have been based upon benign climatic conditions, huge agricultural surpluses and the confiscation of the wealth of other peoples.

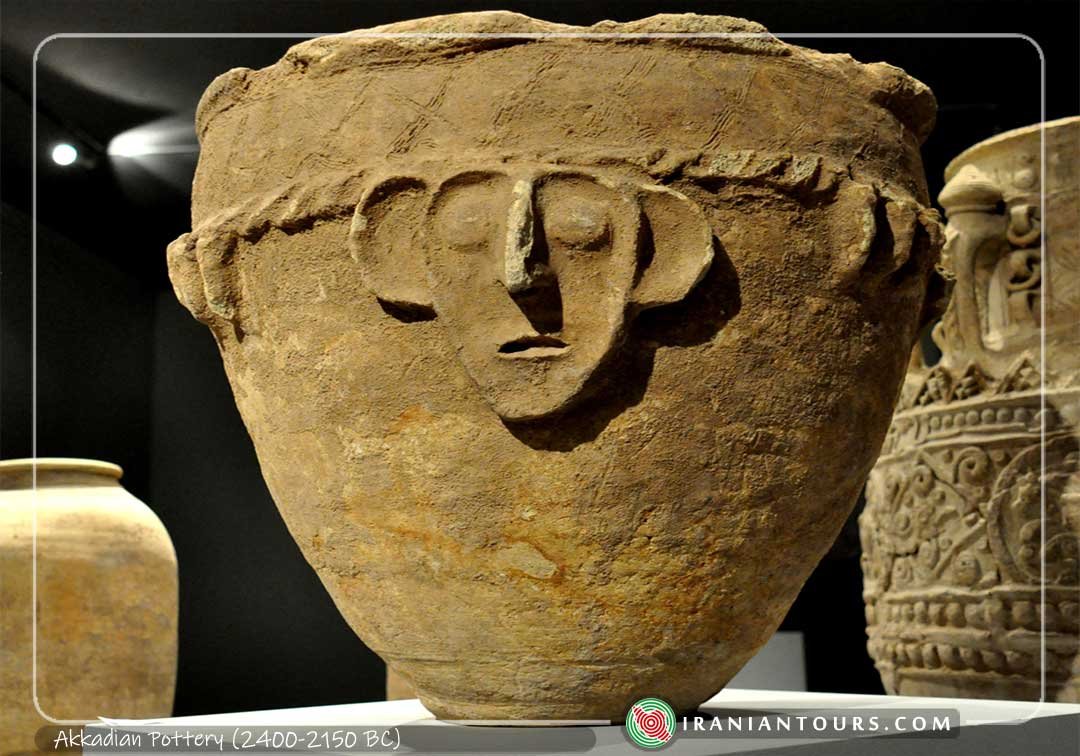

The economy was highly planned. Grain was cleaned, and rations of grain and oil were distributed in standardized vessels made by the city’s potters. Taxes were paid in produce and labour on public walls, including city walls, temples, irrigation canals and waterways, producing huge agricultural surpluses.

In later Assyrian and Babylonian texts, the name Akkad, together with Sumer, appears as part of the royal title, as in the Sumerian LUGAL KI-EN-GI KI-URI or Akkadian Šar māt Šumeri u Akkadi, translating to “king of Sumer and Akkad”. This title was assumed by the king who seized control of Nippur, the intellectual and religious centre of southern Mesopotamia.

During the Akkadian period, the Akkadian language became the lingua franca of the Middle East and was officially used for administration, although the Sumerian language remained as a spoken and literary language. The spread of Akkadian stretched from Syria to Elam, and even the Elamite language was temporarily written in Mesopotamian cuneiform. Akkadian texts later found their way to far-off places, from Egypt (in the Amarna Period) and Anatolia to Persia (Behistun).

Submission of Sumerian kings

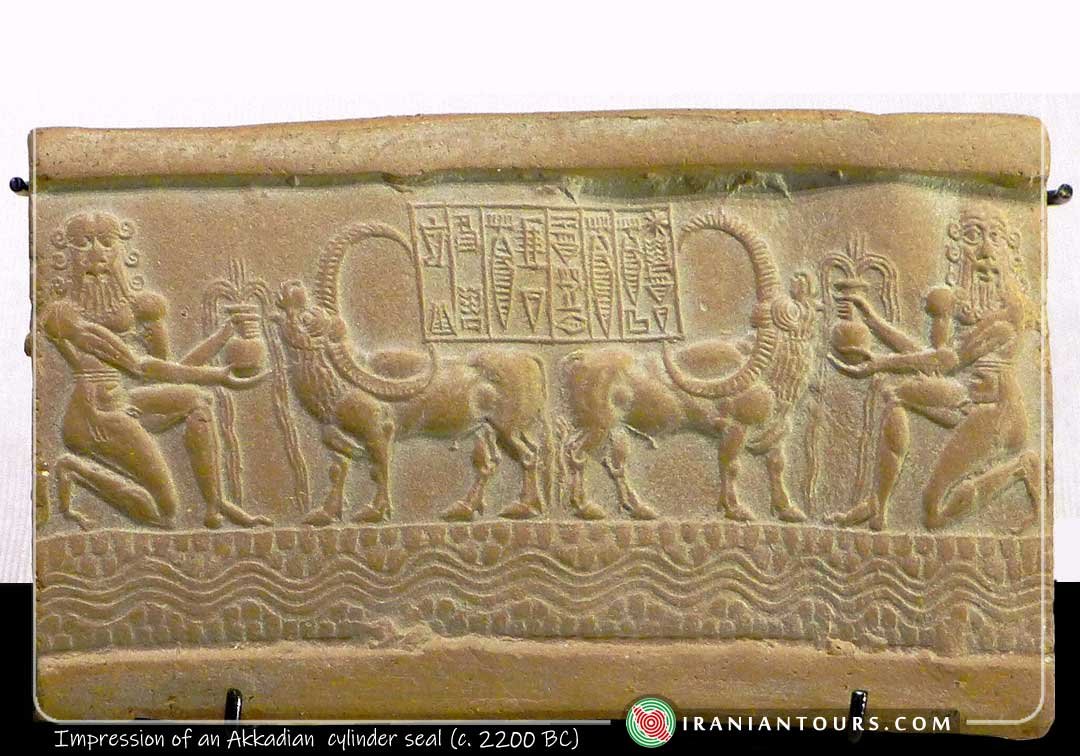

The submission of some Sumerian rulers to the Akkadian Empire is recorded in the seal inscriptions of Sumerian rulers such as Lugal-ushumgal, governor (ensi) of Lagash (“Shirpula”), circa 2230-2210 BCE. Several inscriptions of Lugal-ushumgal are known, particularly seal impressions, which refer to him as governor of Lagash and at the time a vassal (𒀵, arad, “servant” or “slave”) of Naram-Sin, as well as his successor Shar-kali-sharri. One of these seals proclaims:

“Naram-Sin, the mighty God of Agade, king of the four corners of the world, Lugalushumgal, the scribe, ensi of Lagash, is thy servant.”

It can be considered that Lugalushumgal was a collaborator of the Akkadian Empire, as was Meskigal, ruler of Adab. Later, however, Lugal-ushumgal was succeeded by Puzer-Mama who, as Akkadian power waned, achieved independence from Shar-Kali-Sharri, assuming the title of “King of Lagash” and starting the illustrious Second Dynasty of Lagash.

Collapse

The empire of Akkad fell, perhaps in the 22nd century BC, within 180 years of its founding, ushering in a “Dark Age” with no prominent imperial authority until Third Dynasty of Ur. The region’s political structure may have reverted to the status quo ante of local governance by city-states.

Shu-turul appears to have restored some centralized authority, however, he was unable to prevent the empire eventually collapsing outright from the invasion of barbarian peoples from the Zagros Mountains known as the Gutians.

Little is known about the Gutian period, or how long it endured. Cuneiform sources suggest that the Gutians’ administration showed little concern for maintaining agriculture, written records, or public safety; they reputedly released all farm animals to roam about Mesopotamia freely and soon brought about famine and rocketing grain prices. The Sumerian king Ur-Nammu (2112–2095 BC) cleared the Gutians from Mesopotamia during his reign.

The Sumerian King List, describing the Akkadian Empire after the death of Shar-kali-shari, states:

Who was king? Who was not king? Irgigi the king; Nanum, the king; Imi the king; Ilulu, the king—the four of them were kings but reigned only three years. Dudu reigned 21 years; Shu-Turul, the son of Dudu, reigned 15 years. … Agade was defeated and its kingship carried off to Uruk. In Uruk, Ur-ningin reigned 7 years, Ur-gigir, son of Ur-ningin, reigned 6 years; Kuda reigned 6 years; Puzur-ili reigned 5 years, Ur-Utu reigned 6 years. Uruk was smitten with weapons and its kingship carried off by the Gutian hordes.

However, there are no known year-names or other archaeological evidence verifying any of these later kings of Akkad or Uruk, apart from several artefact referencing king Dudu of Akkad and Shu-turul. The named kings of Uruk may have been contemporaries of the last kings of Akkad, but in any event, could not have been very prominent.

In the Gutian hordes, (first reigned) a nameless king; (then) Imta reigned 3 years as king; Shulme reigned 6 years; Elulumesh reigned 6 years; Inimbakesh reigned 5 years; Igeshuash reigned 6 years; Iarlagab reigned 15 years; Ibate reigned 3 years; … reigned 3 years; Kurum reigned 1 year; … reigned 3 years; … reigned 2 years; Iararum reigned 2 years; Ibranum reigned 1 year; Hablum reigned 2 years; Puzur-Sin son of Hablum reigned 7 years; Iarlaganda reigned 7 years; … reigned 7 years; … reigned 40 days. Total 21 kings reigned 91 years, 40 days.

The period between c. 2112 BC and 2004 BC is known as the Ur III period. Documents again began to be written in Sumerian, although Sumerian was becoming a purely literary or liturgical language, much as Latin later would be in Medieval Europe.

One explanation for the end of the Akkadian empire is simply that the Akkadian dynasty could not maintain its political supremacy over other independently powerful city-states.