Timeline

The Medes were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Late 9th to early 7th centuries BC, the region of Media was bounded by the Zagros Mountains to its west, to its south by the Garrin Mountain in Lorestan Province, to its northwest by the Qaflankuh Mountains in Zanjan Province, and to its east by the Dasht-e Kavir desert. Its neighbors were the kingdoms of Gizilbunda and Mannea in the northwest, and Ellipi and Elam in the south.

In the 8th century BC, Media’s tribes came together to form the Median Kingdom, which became a Neo-Assyrian vassal. Between 616 and 609 BC, King Cyaxares (624–585 BC) allied with King Nabopolassar of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and destroyed the Neo-Assyrian Empire, after which the Median Empire stretched across the Iranian Plateau as far as Anatolia.

A few archaeological sites (discovered in the “Median triangle” in western Iran) and textual sources (from contemporary Assyrians and also ancient Greeks in later centuries) provide a brief documentation of the history and culture of the Median state. Apart from a few personal names, the language of the Medes is unknown. The Medes had an ancient Iranian religion (a form of pre-Zoroastrian Mazdaism or Mithra worshipping) with a priesthood named as “Magi”. Later, during the reigns of the last Median kings, the reforms of Zoroaster spread into western Iran.

Brief History

According to the Histories of Herodotus, there were six Median tribes:

Thus Deioces collected the Medes into a nation, and ruled over them alone. Now these are the tribes of which they consist: the Busae, the Paretaceni, the Struchates, the Arizanti, the Budii, and the Magi.

The six Median tribes resided in Media proper, the triangular area between Rhagae, Aspadana and Ecbatana. In present-day Iran, that is the area between Tehran, Isfahan and Hamadan. Of the Median tribes, the Magi resided in Rhagae, modern Tehran. They were of a sacred caste which ministered to the spiritual needs of the Medes. The Paretaceni tribe resided in and around Aspadana, modern Isfahan, the Arizanti lived in and around Kashan (Isfahan Province), and the Busae tribe lived in and around the future Median capital of Ecbatana, near modern Hamadan. The Struchates and the Budii lived in villages in the Median triangle.

The original source for their name and homeland is a directly transmitted Old Iranian geographical name which is attested as the Old Persian “Māda-” (singular masculine). The meaning of this word is not precisely known. However, the linguist W. Skalmowski proposes a relation with the proto-Indo European word “med(h)-“, meaning “central, suited in the middle”, by referring to the Old Indic “madhya-” and Old Iranian “maidiia-” which both carry the same meaning. The Latin medium, Greek méso and German mittel are similarly derived from it.

Greek scholars during antiquity would base ethnological conclusions on Greek legends and the similarity of names. According to the Histories of Herodotus (440 BC): The Medes were formerly called by everyone Arians, but when the Colchian woman Medea came from Athens to the Arians, they changed their name, as the Persians did after Perses, son of Perseus and Andromeda]. This is the Medes’ own account of themselves.

The discoveries of Median sites in Iran happened only after the 1960s. For 1960 the search for Median archaeological sources has mostly focused in an area known as the “Median triangle,” defined roughly as the region bounded by Hamadān and Malāyer (in Hamadan Province) and Kangāvar (in Kermanshah Province). Three major sites from central western Iran in the Iron Age III period (i.e. 850–500 BC) are:

Tepe Nush-i Jan (a primarily religious site of Median period),

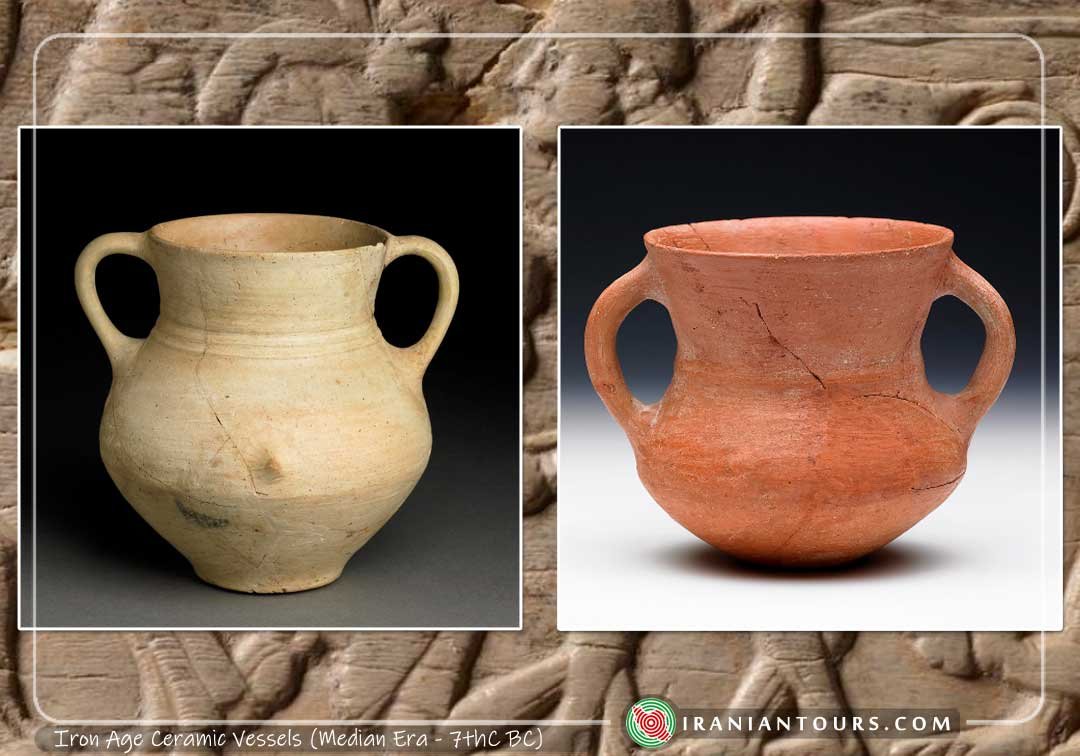

The site is located 14 km west of Malāyer in Hamadan province. The excavations started in 1967 with David Stronach as the director. The remains of four main buildings in the site are “the central temple, the western temple, the fort, and the columned hall” which according to Stronach were likely to have been built in the order named and predate the latter occupation of the first half of the 6th century BC. According to Stronach, the central temple, with its stark design, “provides a notable, if mute, expression of religious belief and practice”. A number of ceramics from the Median levels at Tepe Nush-i Jan have been found which are associated with a period (the second half of the 7th century BC) of power consolidation in the Hamadān areas. These findings show four different wares known as “common ware” (buff, cream, or light red in colour and with gold or silver mica temper) including jars in various size the largest of which is a form of ribbed pithoi. Smaller and more elaborate vessels were in “grey ware”, (these display smoothed and burnished surface). The “cooking ware” and “crumbly ware” are also recognized each in single handmade products.

Godin Tepe (its period II: a fortified palace of a Median king or tribal chief),

The site is located 13 km east of Kangāvar city on the left bank of the river Gamas-Ab. The excavations, started in 1965, were led by T. C. Young, Jr. which according to David Stronach, evidently shows an important Bronze Age construction that was reoccupied sometime before the beginning of the Iron III period. The excavations of Young indicate the remains of part of a single residence of a local ruler which later became quite substantial. This is similar to those mentioned often in Assyrian sources.

Babajan (probably the seat of a lesser tribal ruler of Media).

The site is located in northeastern Lorestan with a distance of roughly 10 km from Nūrābād in Lorestan province. The excavations were conducted by C. Goff in 1966–69. The second level of this site probably dates to the 7th century BC.

These sources have both similarities (in cultural characteristics) and differences (due to functional differences and diversity among the Median tribes). The architecture of these archaeological findings, which can probably be dated to the Median period, show a link between the tradition of columned audience halls often seen in the Achaemenid Empire (for example in Persepolis) and Safavid Iran (for example in Chehel Sotoun from the 17th century AD) and what is seen in Median architecture.

The materials found at Tepe Nush-i Jan, Godin Tepe, and other sites located in Media together with the Assyrian reliefs show the existence of urban settlements in Media in the first half of the 1st millennium BC which had functioned as centres for the production of handicrafts and also of an agricultural and cattle-breeding economy of a secondary type. For other historical documentation, the archaeological evidence, though rare, together with cuneiform records by Assyrian make it possible, regardless of Herodotus’ accounts, to establish some of the early history of Medians.

At the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the Iranian tribes emerged in the region of northwest Iran. These tribes expanded their control over larger areas. Subsequently, the boundaries of Media changed over a period of several hundred years. Iranian tribes were present in western and northwestern Iran from at least the 12th or 11th centuries BC. But the significance of Iranian elements in these regions was established from the beginning of the second half of the 8th century BC. By this time the Iranian tribes were the majority in what later become the territory of the Median Kingdom and also the west of Media proper. A study of textual sources from the region shows that in the Neo-Assyrian period, the regions of Media, and further to the west and the northwest, had a population with Iranian speaking people as the majority.

This period of migration coincided with a power vacuum in the Near East with the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC), which had dominated northwestern Iran and eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus, going into a comparative decline. This allowed new peoples to pass through and settle. In addition Elam, the dominant power in Iran was suffering a period of severe weakness, as was Babylonia to the west.

In western and northwestern Iran and in areas further west prior to Median rule, there is evidence of the earlier political activity of the powerful societies of Elam, Mannaea, Assyria and Urartu. There are various and up-dated opinions on the positions and activities of Iranian tribes in these societies and prior to the “major Iranian state formations” in the late 7th century BC. One opinion (of Herzfeld, et al.) is that the ruling class were “Iranian migrants” but the society was “autonomous” while another opinion (of Grantovsky, et al.) holds that both the ruling class and basic elements of the population were Iranian.

From the 10th to the late 7th centuries BC, the western parts of Media fell under the domination of the vast Neo-Assyrian Empire based in northern Mesopotamia, which stretched from Cyprus in the west, to parts of western Iran in the east, and Egypt and the north of the Arabian Peninsula. Assyrian kings such as Tiglath-Pileser III, Sargon II, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, Ashurbanipal and Ashur-etil-ilani imposed Vassal Treaties upon the Median rulers, and also protected them from predatory raids by marauding Scythians and Cimmerians.

During the reign of Sinsharishkun (622–612 BC), the Assyrian empire, which had been in a state of constant civil war since 626 BC, began to unravel. Subject peoples, such as the Medes, Babylonians, Chaldeans, Egyptians, Scythians, Cimmerians, Lydians and Arameans quietly ceased to pay tribute to Assyria.

Neo-Assyrian dominance over the Medians came to an end during the reign of Median King Cyaxares, who, in alliance with King Nabopolassar of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, attacked and destroyed the strife riven empire between 616 and 609 BC. The newfound alliance helped the Medes to capture Nineveh in 612 BC, which resulted in the eventual collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire by 609 BC. The Medes were subsequently able to establish their Median Kingdom (with Ecbatana as their royal capital) beyond their original homeland and had eventually a territory stretching roughly from northeastern Iran to the Kızılırmak River in Anatolia. After the fall of Assyria between 616 BC and 609 BC, a unified Median state was formed, which together with Babylonia, Lydia, and ancient Egypt became one of the four major powers of the ancient Near East.

Cyaxares was succeeded by his son King Astyages. In 553 BC, his maternal grandson Cyrus the Great, the King of Anshan/Persia, a Median vassal, revolted against Astyages. In 550 BC, Cyrus finally won a decisive victory resulting in Astyages’ capture by his own dissatisfied nobles, who promptly turned him over to the triumphant Cyrus. After Cyrus’s victory against Astyages, the Medes were subjected to their close kin, the Persians. In the new empire, they retained a prominent position; in honour and war, they stood next to the Persians; their court ceremony was adopted by the new sovereigns, who in the summer months resided in Ecbatana; and many noble Medes were employed as officials, satraps and generals.

The list of Median rulers and their period of reign is compiled according to two sources. Firstly, Herodotus who calls them “kings” and associates them with the same family. Secondly, the Babylonian Chronicle which in “Gadd’s Chronicle on the Fall of Nineveh” gives its own list. A combined list stretching over 150 years is thus:

- Deioces (700–647 BC)

- Phraortes (647–625 BC)

- Scythian rule (624–597 BC)

- Cyaxares (624–585 BC)

- Astyages (585–549 BC)

However, not all of these dates and personalities given by Herodotus match the other near eastern sources.

In Herodotus (book 1, chapters 95–130), Deioces is introduced as the founder of a centralised Median state. He had been known to the Median people as “a just and incorruptible man” and when asked by the Median people to solve their possible disputes he agreed and put forward the condition that they make him “king” and build a great city at Ecbatana as the capital of the Median state.] Judging from the contemporary sources of the region and disregarding the account of Herodotus puts the formation of a unified Median state during the reign of Cyaxares or later.