Timeline

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia, also referred to as the Safavid Empire, was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The Safavid shahs established the Twelver school of Shia Islam as the official religion of the empire, marking one of the most important turning points in Muslim history.

The Safavid dynasty had its origin in the Safavid order of Sufism, which was established in the city of Ardabil in the Azerbaijan region. It was an Iranian dynasty of Kurdish origin but during their rule, they intermarried with Turkoman, Georgian, Circassian, and Pontic Greek dignitaries. From their base in Ardabil, the Safavids established control over parts of Greater Iran and reasserted the Iranian identity of the region, thus becoming the first native dynasty since the Sasanian Empire to establish a national state officially known as Iran.

The Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1722 (experiencing a brief restoration from 1729 to 1736) and, at their height, they controlled all of what is now Iran, Azerbaijan Republic, Bahrain, Armenia, Eastern Georgia, parts of the North Caucasus, Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan, as well as parts of Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Despite their demise in 1736, the legacy that they left behind was the revival of Iran as an economic stronghold between East and West, the establishment of an efficient state and bureaucracy based upon “checks and balances”, their architectural innovations and their patronage for fine arts. The Safavids have also left their mark own to the present era by spreading Twelver Islam in Iran, as well as major parts of the Caucasus, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia.

Brief History

Timeline

- 1500 : Overthrow of the Timurids by the Safavid leader Ismail, at that time only 15 years old

- 1512 : Shiism is proclaimed as the state religion of Iran

- 1514-1555 : Safavid was with Ottomans

- 1514 : Shah Ismail defeated at Chaldoran

- 1515 : Portuguese strategist, Alfonso de Albuguese captures the island of Hormuz at the moth of the Persian Gulf

- 1520-1566 : The rule of Sultan Soleiman the Magnificient of Turkey

- 1534 : Ottoman forces threaten Tabriz under the rule of Shah Tahmasb

- 1542-1605 : The rule of Akbar Shah in India

- 1555 : Safavid capital is moved to Qazvin

- 1558-1643 : The rule of Queen Elizabeth in England

- 1564-1615 : The life of William Shakespeare

- 1582 : A new Georgian calendar is instituted by Pope Gregory

- 1587-1628: The rule of Shah Abbas the Great

- 1589-1610 : The rule of Henry IV in France

- 1598 : Shah Abbas chooses Isfahan as his capital

- 1602 : The Dutch East India Company sends its first ships to Asia

- 1603-1625 : The rule of England’s James I, the first king to rule over the United Kingdom

While the Turkman dynasties ruled in Azerbaijan, Sheikh Heydar headed a movement that had begun in the late 13th century as a Sufi order under his ancestor, Sheikh Safi al-Din of Ardabil, who claimed descent from the Seventh Shiite Imam, Musa al-Kazem. By the end of the 15th century, this Sufi order was turned into a militant movement with numerous followers, mainly from the Turkman tribesmen of Anatolia. They were called the Qizil-Bash (“Red Heads”) because of the distinctive red headgear that they had adopted to mark their adherence to the Safavids. With their help, the Safavids conducted several successful military campaigns, especially in the Caucasus. By virtue of their descent from the Prophet’s family, the Safavid movement was invested with a semi-sacred character, and the religious character of the new claimants to the throne was particularly acceptable to the Persians. When Sheikh Heydar was killed in one of his battles in the Caucasus, his son Ismail avenged his death by conquering Azerbaijan and then the whole of Iran. In 1501, Ismail was proclaimed Shah of Iran.

He became the founder of one of the most famous ruling dynasty in Iranian history — the Safavids. The Safavids declared Shiite Islam the state religion and used proselytizing and force to convert the large majority of Muslims in Iran to the Shiite sect. Their main external enemies were the Uzbeks and the Ottomans. The Uzbeks were an unstable element along Iran’s northeastern frontier, raiding Khorasan and block-ing the Safavid advance northward into Transoxiana. The Ottomans, who were Sunnites, were rivals for the religious allegiance of Muslims in eastern Anatolia and Iraq and pressed territorial claims in both these areas and in the Caucasus. A series of battles between Iran and the Ottoman Turkey lasted throughout the reign of the Safavids. Tahmasb, the eldest son and successor of Shah Ismail, had none of his father’s appeal or personal courage. For a long period after coming to the throne, he was a pawn of powerful tribal leaders. He is remembered for the unusual length of his reign (fifty-two years), his treachery in selling his guest Bayazid, son of the Ottoman Sultan Soleiman the Magnificent, to his father in exchange for 400,000 pieces of gold, and for a mention (as “Bactrian Sophi”) in John Milton’s Paradise Lost. The political history of his reign is characterized by petty intrigues. However, its art history, especially the arts of the book, is rich and compelling. During his reign, Qazvin was chosen a capital as being a less vulnerable city compared to Tabriz, the first capital of Safavids. The decade after Tahmasb’s death (he was poisoned by one of his wives) was characterized by political turbulence. After endless plotting and sever-al assassinations, his fourth son ascended the throne as Ismail II. Ismail had been held in prison by his father for twenty-five years. Demented by incarceration and eventually fatal drug addiction, he began his reign by extirpating his rivals. He ordered that his brother, the purblind and seemingly innocuous Mohammad Khodabandeh, and Mohammad’s young son Abbas be assassinated. However, before this order could be carried out, Ismail suddenly died, perhaps of drink and an overdose of opium.

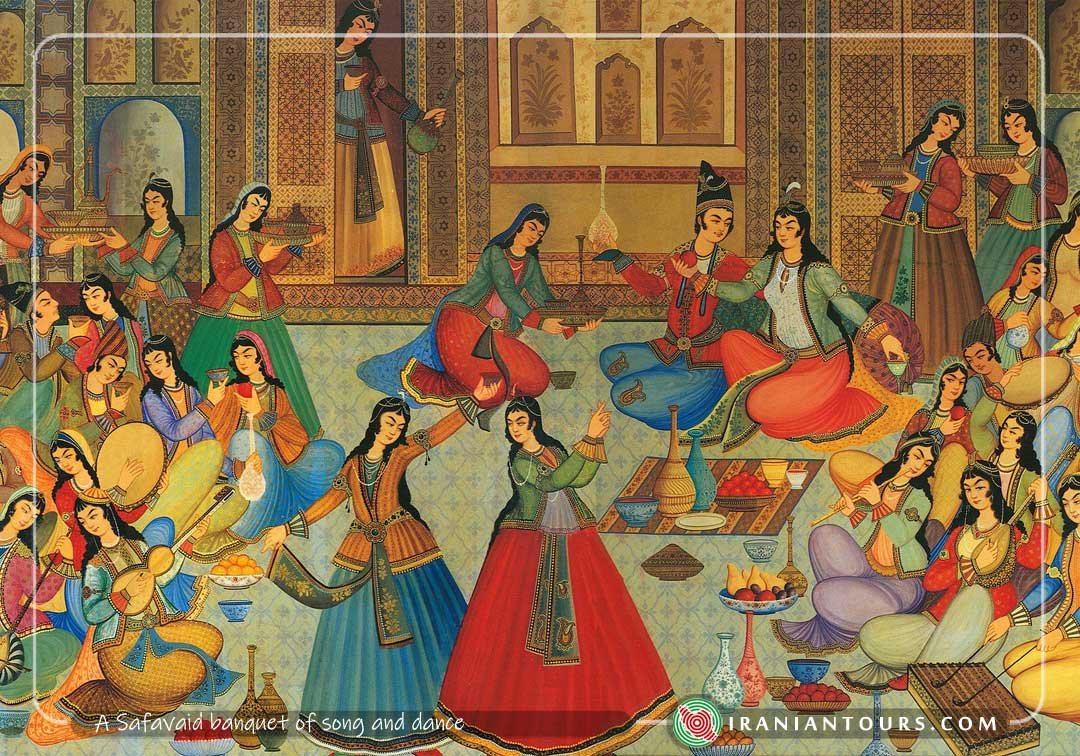

Some authorities, however, say that he was assassinated by a conspiracy of dissident feudal chiefs. His successor, the feeble Mohammad Khodabandeh, ruled only in name. For two years, his energetic wife tried to bring the shah’s vassals under control. When she proved too threatening, the vassals murdered her, and for eight years Iran was dismembered in bitter, fratricidal feuds. The Safavid state was saved by Mohammad’s son, Shah Abbas I, who is better known in Iranian historical tradition as Shah Abbas the Great. Shah Abbas started his career by signing a largely disadvantageous treaty with the Ottomans. This treaty, however, allowed him to gain breathing space to confront and defeat the Uzbeks. With the advice of Robert Shirley, an English adventurer versed in artillery tactics, he reorganized the army and equipped it on European lines. He then fought several successful battles with the Ottomans, reestablishing Iranian control over Iraq, Georgia, and parts of the Caucasus. He also strengthened the bureaucracy and further centralized the administration. Shah Abbas transferred the capital from Qazvin to Esfahan, a centrally located city, from where he could control his vast territories more successfully. This monarch, a contemporary of King James I of England and King Henry IV of France, was not only great as a warrior and administrator, but he also fostered a renaissance of art. The period of his reign brought forth the golden age of Esfahan, which was turned into one of the world’s most beautiful cities, worthy of its title “Half the World”. Under Abbas’s patronage, carpet-weaving became a major industry, and fine Persian rugs appeared in the homes of wealthy Europeans. Another profitable export was textiles, including brocades and damasks of unparalleled richness. The production and sale of silk were made a monopoly of the crown. In the illumination of manuscripts, bookbinding, and ceramics, the work of this period is outstanding. In painting, it is one of the most notable in Persian history. Shah Abbas was a patron of science and scientific achievements as well. Some of the greatest philosophers of Iran lived under his rule, among them Mullah Sadra, Mir Damad, and Moqaddas Ardabili. Shah Abbas’s enthusiasm for the building was not confined to Esfahan. The extension and restoration of the famous shrine of Imam Reza in Mash-had and the construction, along the swampy littoral of the Caspian Sea, of the celebrated stone causeway were among his other notable achievements. There is hardly a part of Iran where either Safavid buildings or major Safavid restorations cannot be found. The dynasty spent a great deal of money and effort on the building of bridges, roads, and caravansaries to encourage trade. To facilitate commerce and find a way to southern seas, Shah Abbas expelled the Portuguese, who had previously occupied Bahrain and the island of Hormoz, trying to dominate the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf trade. He also freed and expanded the port that became known as Bandar Abbas, which is function-ing even now. After Shah Abbas, the centralized rule started to decline. It is hardly surprising that Chardin saw Shah Abbas’s reign as the golden age of Iran. “When this great prince ceased to live”, he wrote, “Persia ceased to prosper”. And indeed, the Safavid state never achieved the degree of political and military power, economic prosperity, internal stability and security, and artistic distinction that it had under Shah Abbas. Of Shah Abbas’s successors, only Abbas II, the great-grandson of his namesake, interrupted the steady decline of the dynasty. He was crowned at a very early age and thus successfully escaped the seclusion of the harem, which may well be the reason why he developed more favourably than the other of Shah Abbas’s successors. Although inclined to lose control under the influence of alcohol and narcotics, he was more gifted than any other descendant of Shah Abbas the Great, and history records him as a just ruler and an intelligent patron of arts. Abbas II died in 1667 at the age of thirty-three. Abbas’s eighteen-year-old son ascended the throne as Shah Safi. However, shortly after his accession, the shah fell ill. The doctors ascribed his illness to the miscasting of his horoscope at the time of his accession. Therefore on a day proclaimed by the astrologers as unlucky, a mock coronation of a Zoroastrian was performed. The following day, allegedly a lucky one, an effigy of the Zoroastrian was decapitated, and Shah Safi reassumed his throne as Shah Soleiman. Soleiman’s harem upbringing had left him under the thumb of the eunuchs. Like most of the Safavid rulers, he cared more about women and wine than his country. Chardin reported that he could drink any Swiss or German under the table. The Soleiman’s reign was, for the most part, peaceful, though it was not the ruler’s merit but rather a fortunate culmination of circumstances. The last ruling Safavid monarch was Shah Sultan Hossein. In character, he was pious, humane, and feeble. His piety earned him the nicknames of “Mullah Hossein” and “Yashki dir” (Turkish: “It is good”), the second deriving from his invariable reply of assent to every proposal made by the clergy. His feeble-ness accelerated the decline of the country. Once again the eastern frontiers began to be breached, and a small body of Afghan tribesmen led by Mah-mud, a former Safavid vassal in Afghanistan, won a series of easy victories before taking the capital. Although the Safavid dynasty claimed rule for many following years, bearing illustrious but hollow names like Tahmasb II and Abbas III, the glory of the Safavid reign was never re-established.